Chuck D. Bones

Circuit Wizard

In this part, we'll discuss what happens when we put a resistor in parallel with a pot. We'll address the simple case where we use the pot as a variable resistor (as opposed to a variable divider) where we connect two pins together.

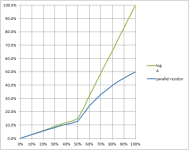

The first example is a B-taper pot. We'll connect pins 1 & 2 together and put a resistor of equal value across from pin 1 to pin 3. Let's say it's a 100K resistor in parallel with a 100K pot. The actual resistor value doesn't matter, only it's relationship with the pot value matters. The green line is the % resistance vs. % rotation with no parallel resistor. The blue line is the total % resistance vs. % rotation when there is a resistor in parallel. As we would expect, at 100% rotation we get 1/2 of the resistance because that's what you get when you put two equal resistors in parallel. Every other point on the blue line represents the total resistance we get when the pot resistance is less than the parallel resistor. Notice that below 10% rotation, the green & blue lines converge, indicating that the parallel resistor has little or no effect on the total resistance. Also notice the shape of the blue line, it curves so that the top side of the line is convex. This is the opposite direction of curvature compared to A- or C-taper. This is visual proof that we cannot make an A- or C-taper pot from a B-taper pot. The resulting curve bends the wrong way. It doesn't matter what value resistor you choose.

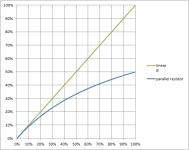

So what happens when we put a resistor in parallel with an A-taper pot? We get a less extreme A-taper. In the plot below, the green line is the resistance with no parallel resistor and the blue line is the resistance with an equal value resistor in parallel. Up to 50% rotation, there is very little difference between the two curves. But from 50% rotation on up, the blue curve is not nearly as steep as the green curve. I have done this on occasion, when I want a pot that behaves like A-taper at the bottom end of rotation, but is more like B-taper at the top end of rotation. C-taper works the same way, except the direction of rotation is reversed.

The first example is a B-taper pot. We'll connect pins 1 & 2 together and put a resistor of equal value across from pin 1 to pin 3. Let's say it's a 100K resistor in parallel with a 100K pot. The actual resistor value doesn't matter, only it's relationship with the pot value matters. The green line is the % resistance vs. % rotation with no parallel resistor. The blue line is the total % resistance vs. % rotation when there is a resistor in parallel. As we would expect, at 100% rotation we get 1/2 of the resistance because that's what you get when you put two equal resistors in parallel. Every other point on the blue line represents the total resistance we get when the pot resistance is less than the parallel resistor. Notice that below 10% rotation, the green & blue lines converge, indicating that the parallel resistor has little or no effect on the total resistance. Also notice the shape of the blue line, it curves so that the top side of the line is convex. This is the opposite direction of curvature compared to A- or C-taper. This is visual proof that we cannot make an A- or C-taper pot from a B-taper pot. The resulting curve bends the wrong way. It doesn't matter what value resistor you choose.

So what happens when we put a resistor in parallel with an A-taper pot? We get a less extreme A-taper. In the plot below, the green line is the resistance with no parallel resistor and the blue line is the resistance with an equal value resistor in parallel. Up to 50% rotation, there is very little difference between the two curves. But from 50% rotation on up, the blue curve is not nearly as steep as the green curve. I have done this on occasion, when I want a pot that behaves like A-taper at the bottom end of rotation, but is more like B-taper at the top end of rotation. C-taper works the same way, except the direction of rotation is reversed.